EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The African Development Bank’s Dakar II initiative, ‘Feed Africa: Food Sovereignty and Resilience’, is the latest and most ambitious addition to the bank’s longstanding Feed Africa program. The initiative aims to transform African agriculture and turn Africa into a breadbasket for the world. Delivered through national agricultural development plans for 40 African countries, the initiative has sparked significant debate regarding its approach and potential impacts. The initiative seeks to industrialise African food systems with a proposed budget of $61 billion, primarily sourced from the private sector and development institutions. However, this strategy has been criticised for potentially marginalising small-scale farmers, undermining biodiversity, and fostering dependency on multinational corporations for seeds and agrochemicals.

To better understand the Dakar II Initiative, the Alliance for Food Sovereignty in Africa (AFSA) analysed each of the 40 “country compacts” – the comprehensive agricultural development plans developed by consultants for the program. We examined critical factors, including funding, land allocation, seeds, agrochemical use, technology, and people, to assess their collective implications for Africa’s small-scale farmers. In this report, we present the essential findings and the concerns they raise.

Critics, including the President of Ireland, have voiced concerns over the initiative’s one-size-fits-all approach and its emphasis on large-scale monocropping, formal seed systems, and high-tech solutions such as climate-smart agriculture, digital and precision agriculture, and chemical inputs. These methods are argued to be out of reach for small-scale farmers due to their cost, risk to the environment, and threat to their autonomy and traditional practices.

The Alliance for Food Sovereignty in Africa (AFSA), representing a coalition of 41 member networks across 50 countries, has emerged as a vocal critic of the Dakar II compacts. AFSA advocates for a shift towards agroecology and food sovereignty, emphasising the importance of sustainable agriculture and the empowerment of small-scale farmers. With an impact on approximately 200 million individuals, AFSA’s stance underscores a significant pushback against the Green Revolution-style industrialisation of agriculture and calls for a re-evaluation of strategies to unlock Africa’s agricultural potential.

In summary, while the Dakar II initiative represents a significant investment in the future of African agriculture, its current trajectory raises concerns about inclusivity, environmental sustainability, and the long-term viability of small-scale farming. A recalibration towards more holistic, inclusive, and sustainable approaches, such as agroecology, is necessary to ensure that the development of African agriculture benefits all stakeholders and preserves the continent’s rich biodiversity and agricultural heritage.

Key Criticisms:

- One-Size-Fits-All Approach: The Dakar II Compacts demonstrate a one-size-fits-all approach to agricultural development, overlooking the diverse needs and contexts of African countries and their farmers. This uniform strategy of agricultural industrialisation risks side-lining small-scale farmers who are vital to the continent’s food security and cultural heritage.

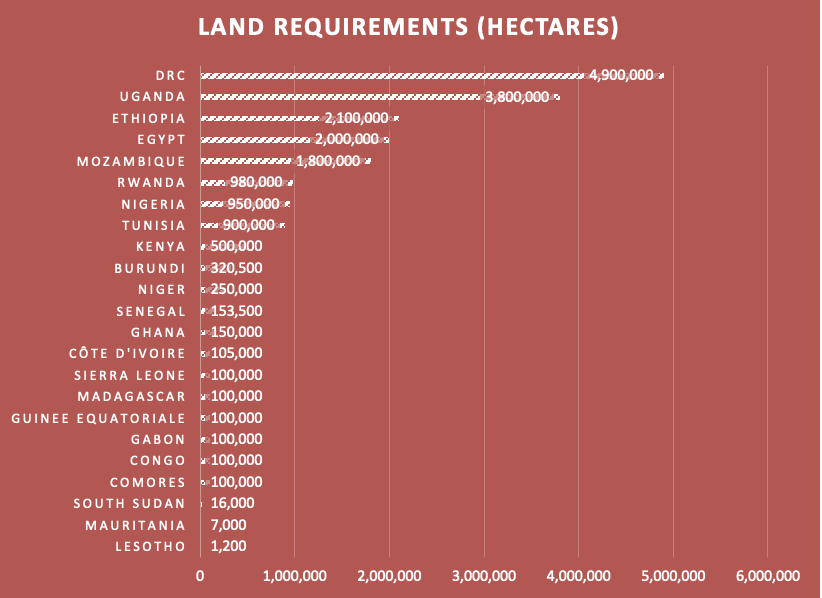

- Threats to land rights and the environment: The cumulative total of proposed land area to be put into industrial production is over 25 million hectares, or 257,000 sq. km – an area larger than the size of Ghana or Uganda. This risks massive smallholder displacement through land-grabbing and increased pressure on the environment from unsustainable industrial agriculture on currently uncultivated land.

- Marginalisation of Small-Scale Farmers: The emphasis on large-scale monocropping and formal seed systems poses challenges for small-scale farmers in sustaining their food security and preserving biodiversity. This approach marginalises the importance of locally significant foods and strips away their cultural significance. By prioritising formal seed systems and high-tech solutions, there is a risk of increasing dependency on multinational corporations and eroding traditional seed-saving practices.

- Threats to Biodiversity: The initiative’s emphasis on high-yielding, uniform crop varieties in formal seed systems, coupled with the promotion of chemical fertilisers and pesticides, poses significant threats to both biodiversity and sustainable agriculture. This approach risks diminishing traditional crop diversity, indigenous seed varieties, and valuable genetic resources while raising concerns about environmental sustainability, affordability, farmer autonomy, and exacerbating inequalities.

- Dependency and Control: There are significant worries about increased dependency on multinational seed companies or government agencies due to reliance on formal certified seed systems. This dependency could undermine farmers’ autonomy and resilience, making them reliant on external sources for their seed needs.

Recommendations:

- Re-evaluate the Initiative’s Approach: It is crucial to assess the Dakar II initiative’s strategies to ensure they are inclusive, sustainable, and tailored to the specific needs of diverse African countries and their farmers.

- Protect smallholder land rights: Existing land users must be protected from arbitrary dispossession of their lands for large-scale industrial agriculture projects, in line with protections provided by the African Union’s Land Governance Strategy, the Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests, and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas

- Promote Agroecology: A shift towards agroecology is recommended to move away from dependency and insecurity towards a decolonised agronomy. Agroecological models offer a path that supports diverse agricultural development and empowers small-scale farmers by providing a viable, nutritious, affordable and sustainable alternative to industrial agriculture.

- Adopt Inclusive and Participatory Approaches: Policies and investments should prioritise the needs and voices of small-scale farmers, ensuring they have access to resources, knowledge, and markets. Decision-making processes should be more inclusive and participatory, considering the diverse perspectives of farmers and other stakeholders, to ensure that agricultural development is aligned with the priorities of African farmers and communities.

- Preserve Agricultural Biodiversity: Efforts should be made to preserve agricultural biodiversity by supporting the maintenance of a rich variety of crops and breeds managed by small-scale food producers. This approach would ensure the resilience of smallholder farmers and the environmental sustainability upon which they depend.

###

Download full report in PDF here

1. INTRODUCTION

Nearly two decades into the New Green Revolution for Africa, agricultural development on the continent is at a crossroads. A recent report has shown that the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA), which has for the past 18 years sought to achieve agricultural development in Africa through industrialisation and large-scale intensification of African food systems, is failing on its own terms (Blair et al., 2021) and the organisation has dropped the term Green Revolution from its name to just become AGRA. Alarmingly, sub-Saharan Africa is the only world region where undernourishment has not decreased since 2005, when AGRA was founded (FAO et al., 2023). Indeed, the number of chronically hungry has increased by 50%, not declined by 50% as promised by AGRA.

Similarly, the New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition (NAFSN) was launched in 2012 by the G7 countries as a major initiative to fight hunger in Africa. It promised to raise 50 million people out of poverty over the next ten years by brokering pro-market reforms and flows of private capital to African agriculture. However, it failed to fulfil its promises and disappeared quietly from the public arena before the end of the 10-year period (Praskova & Novotny, 2021).

In the wake of poor progress in hunger alleviation and improved livelihoods for smallholder farmers, new efforts are emerging to tackle these issues. One such effort has been the Dakar II Summit, titled ‘Feed Africa: Food Sovereignty and Resilience,’ held In January 2023 by the African Development Bank and the Government of Senegal. The summit was attended by “dozens of dignitaries, including 34 heads of state and government, 70 government ministers, and development partners” (AfDB, 2023a). The overall goals of the summit were to increase food security and productivity in Africa, limit import dependency, and turn Africa into “a breadbasket for the world” (AfDB, 2023a).

The African Development Bank (AfDB) has been a key agricultural player for many years. As early as 1997, the agricultural sector was classified as strategic by the AfDB. To date, 1,161 agriculture-related projects have been finalised or approved, for the equivalent of USD 18.4 billion. In 2022, this sector accounted for 23% (USD 1.9 billion) of AfDB loans, grants and equity investments as well as approved guarantees. The Feed Africa program took the lion’s share with 1.7 billion. These funds have been used to build or rehabilitate 1,682 km of roads and provide 2,605 tons of agricultural inputs (fertilisers, seeds, pesticides). Between 2016 and 2025, AfDB’s “Feed Africa” programme planned an investment of 24 billion dollars to transform African agriculture (GRAIN,2023).

The African Development Bank published 40 “Country Food and Agriculture Delivery Compacts” to map the paths to achieving the bold goals of the Dakar II summit. These compacts sought to produce “time-bound and clearly measurable indicators for success, including concrete national policies, incentives, and regulations to establish an enabling environment for wider and accelerated investments across the agriculture sector” (AfDB, 2023b).

Each Compact follows a standardised format. First, the local country context is provided, looking at rates of hunger and domestic food production. Next, current challenges are listed, often demonstrating how hunger and economic shocks have increased in recent years. Third comes research on existing government policies for agricultural development. Finally, the compacts lay out their roadmap of solutions to achieve goals of higher food security and lower food imports over the next five to ten years. This final section sometimes comes with the commitment and collaboration of governments and funding partners, building on existing plans and creating new ones.

To reach their goals, the compacts “set targets for self-sufficiency in specific agricultural value chains, define efficient and effective road maps – of seed systems, competitive production, market access, extension, policy reforms… results-based financing, key partners and performance contracts” (AfDB, 2023a). A common strategic approach of the compacts is the development of Special Agro-Industrial Processing Zones (SAPZs), called ‘agropoles’ in Francophone countries. These are designed to boost agricultural productivity and competitiveness by concentrating agro-processing activities in areas with high agricultural potential. These zones facilitate the integration of production, processing, and marketing efforts by bringing together agricultural producers, processors, aggregators, and distributors in a single location to reduce transaction costs and enhance business services. By equipping rural areas with essential infrastructure, SAPZs attract private investment, driving social and economic development (Nigeria Compact).

Across the 40 participating countries, a broad spectrum of social, ecological, and agricultural frameworks exists. Despite this diversity, the approaches prescribed by the initiatives are strikingly homogeneous. This approach mirrors the Green Revolution for Africa, adopting a universal solution model for agricultural development that fails to consider the different contexts and landscapes. The emphasis on principal commodity crops, mechanised farming tools, and standardised land tenure systems condenses the practices into a uniform effort aimed at agro industrialisation.

These 40 compacts represent significant mobilisation of resources. From the summit alone, the AfDB’s website claims that $36 billion was raised to achieve the goals of the compact, including $10 billion from the AfDB, $7 billion from the Islamic Bank, $5 billion from USAID, $4 billion from the EU, and $3 billion from the International Fund for Agricultural Development (AfDB, 2023a). Latest reports from AfDB claim it has “mobilised over $70 billion in an unprecedented global effort” (AfDB, 2024).

This investment alone is more than anything previously spent on New Green Revolution efforts for agricultural development on the continent. With such a large amount of money purportedly poured into them, the compacts signal a new era for the development of African agriculture. With such an enormous potential to alter food systems on the continent, a critical analysis of what the compacts are calling for is needed. This study will examine what kind of solutions the compacts propose for African agriculture, where the money attached to them is being directed, and how the compacts’ initiatives will affect small-scale farmers.

2. METHODS

All 40 compacts were reviewed for this study, as well as supplemental grey literature from the AfDB about the summit. After a few initial compacts were examined to better understand what information they contained, we analysed three key factors (money, land, and people) across the 40 compacts. We compiled the results for the compacts that reported such data relating to three main variables. Specifically, the data included the total cost of each compact, what the money was allocated for, where the money is coming from, how much new land is to be put into cultivation, how much new land is to be irrigated, and how many people are to be included in new industrialised production programs. Additionally, other data that did not fit into these categories yet got at our key research questions was collected along the way, including seeds, agrochemicals and technology.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1 MONEY

Altogether, the 40 compacts representing 40 African countries across all regions of the continent call for an additional $61 billion to industrialise African food systems. That number alone is bigger than the GDP of more than 40 African countries. This number represents both committed funds and money to be raised from national governments, the private sector, development institutions, and farmers’ organisations.

While it is hard to tell exactly where this money is supposed to come from, it is estimated that the private sector will finance at least a quarter of the total budget. This significant dependence on the private sector risks underfunding the plans if firms fail to invest, and if they do, it opens the door for corporations to reshape African agriculture to their interests. While this has been ongoing, the compacts, as mentioned earlier, hold the potential to greatly accelerate this process and cement the dominant role of industry in small-scale production. For example, in Nigeria, the Compact seeks to support existing private sector partners, including “Sahel consulting, Seed companies, TATA/JD, NAMEL, TROTRO, ALLUVIAL AFEX, Baban Gona, Sasakawa Global, Psaltry International, Flour Mills of Nigeria, Nestle, Kellogg’s, WAMCO CamPinaetc” (Nigeria Compact). These funders represent tractor companies and multinational corporations such as Nestle and Kellogg’s, all with their own commercial interests that don’t necessarily correlate with food sovereignty in Africa. In addition, the compact references “seed companies” broadly, with little transparency as to who is seeking to control African seed systems.

Other key funders of the compacts are development institutions and organisations. These include the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, AGRA, USAID, FAO, IFAD, JICA, the EU, the World Bank, the AfDB, and others. While these organisations may seem to represent a distinct category of interests, their efforts align with the private sector much more than the needs of small-scale farmers. Over the past 25 years, the AfDB has targeted agro-industrialisation as a key development strategy, with agricultural projects accounting for one-fourth of its total spending in 2022. However, many of the AfDB’s agricultural projects have been criticised on social and ecological grounds for allowing multinational corporations to exercise their power, and profit at the expense of farmers and the environment (GRAIN, 2023).

The chart below sets out the proposed budget requirements anticipated to achieve the results in each of the 35 country compacts where firm figures were provided. The figures are total cost per country in millions of US Dollars. These add up to more than 61 billion USD for the 10-year program. See Appendix A for more details.

Regarding where the money is allocated, the compacts promote large-scale and industrial models of agricultural development. Despite a stated desire of the summit for Africa to feed itself, the compacts repeatedly promote commodity crops meant for export, both on and off the continent. This can be most noticeably seen in northern Africa, where the Middle East, rather than African countries, becomes the main destination for locally grown food (Somalia and Mauritania Compacts).

Regarding where the money is allocated, the compacts promote large-scale and industrial models of agricultural development. Despite a stated desire of the summit for Africa to feed itself, the compacts repeatedly promote commodity crops meant for export, both on and off the continent. This can be most noticeably seen in northern Africa, where the Middle East, rather than African countries, becomes the main destination for locally grown food (Somalia and Mauritania Compacts).

The compacts also emphasise a small number of internationally traded commodity crops. Maize, rice, soybeans, wheat, and oilseeds dominate the compacts, to be grown through large-scale monocropping. However, this approach poses challenges for farmers in maintaining crop and dietary diversity, sustaining their food security and preserving biodiversity crucial for soil health and robust agroecosystems.

Although the compacts detail the critical issue of hunger in many countries, they consistently promote crops more suited for animal feed than human consumption. This focus is driven by the profit potential for agribusiness and seed companies rather than the imperative to nourish populations. Despite occasional nods towards crops more relevant to local diets, such as cassava, horticulture, yam, and fruit, these gestures are overshadowed by the predominant push for cash crops. This emphasis not only marginalises the importance of locally significant foods but also strips away their cultural significance as efforts are made to adapt traditional crops for global markets.

The compacts aspire to make African agriculture and livestock vibrant sectors driving economic growth and economic diversification. However, they overlook the essential component of agricultural biodiversity, which is crucial for the resilience of smallholder farmers. By prioritising economic diversification over the preservation of a rich variety of crops maintained by smallholders, the agreements not only jeopardise the livelihoods of these farmers but also threaten the environmental sustainability upon which they depend. This approach undermines both the well-being of small-scale farmer communities and the ecological balance necessary for their survival.

3.2 LAND

For the 23 compacts that provided data on land requirements, the plans call for 25.7 million hectares to be brought into industrial production, much of it on new or “underutilized” land for large agribusiness-led block farms. More than 6 million hectares are slated for irrigation to support industrial-scale farms. The total land requirement is over 257,000 sq. km – equivalent to a land area larger than Ghana or Uganda.

To the extent that expansion is on land already being used by farmers, herders or other rural producers, it represents a threat to their land rights. To the extent the program is bringing new land into production, it presents a threat to the environment, an abandonment of any pretence of “sustainable intensification” based on raising smallholders’ productivity.

The proposed expansion of land under industrial cultivation is a familiar narrative of AfDB President Akinwumi Adesina. He has often lamented the fact that Africa is underutilising its arable land, which is claimed to account for 65% of the total uncultivated arable land left on earth (Adesina, 2022). He outlined his vision to a USDA audience, “Africa’s savannah, estimated at 600 million hectares, of which 400 million hectares can be farmed, has been called Africa’s largest forgotten asset. Only 10% of this massive land area is cultivated. What Africa needs to do is transform its savannahs, just like Brazil did and become a global powerhouse in food and agriculture” (Adesina, 2018). It is instructive to note that AfDB President Adesina gained his PhD in Agricultural Economics from Purdue University in the US Corn Belt State of Indiana, and that he refers to Norman Borlaug (“the Father of the Green Revolution”) as his mentor.

The Congo Basin is the world’s second-largest rainforest. The Basin comprises Cameroon, Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Republic of Congo, Equatorial Guinea and Gabon. It covers close to 70% of the forestlands of Africa. Of the 530 million hectares in the Congo Basin, 300 million are composed of forests: 99% of these are primary or naturally regenerated forests, as opposed to plantations. Slash-and-burn agriculture, commercial farming, and the development of infrastructure to open up the forest zones, together with the construction of secondary agricultural roads are the main causes of deforestation (CIFOR/ICRAF, 2015). The world’s rainforests absorb huge amounts of carbon dioxide, slowing down global warming. According to researchers at the University of Ghent, the rainforest in the Democratic Republic of Congo is the most important rainforest carbon sink in the world – more important even than the Amazon in South America (The Congo Basin Forest Partnership (CBFP), 2023). The Dakar II compacts show that, in just three of the six Congo Basin countries, over five million hectares of land is targeted for agro-industrialisation, (DRC 4,900,000 ha, Congo 100,000 ha, Gabon 100,000 ha). This 51,000 sq. km area – around twice the size of Rwanda – will be transformed into industrial production in Congo Basin’s largely forested countries. This potential wave of large scale land acquisitions by private sector investors risks accelerating the deforestation of the Earth’s second lung, and displacing millions of land users.

The chart below shows the area of land proposed to be transformed (in hectares) according to those 23 country compacts in which definite figures have been provided. As such, we should treat this as a low estimate since it includes data from just over half of the countries. See Appendix B for more details.

Many compacts assert that if the land is not used for large-scale commercial monocropping, it is being used improperly. For example, in Rwanda, “land fragmentation” is cited in the Compact as a critical barrier to development because farmers’ “plots are too small to produce a marketable surplus to invest in future production” (Rwanda Compact). In Lesotho, the compact notes how most land is held traditionally, with most transfers of land occurring informally. As a result, “there is no comprehensive land registry, nor a database of agricultural land parcels. This effectively prohibits the use of land for collateral, especially given the uncertainty relating to the transferability of leases and the reputational risk that a lending institution would incur were it to have to repossess land” (Lesotho Compact). Here, we see smallholder-held land become ‘collateral’ in debt schemes from large corporations. In Ghana as well, “the land tenure system is a key agriculture and crop production challenge… It is a constraint to crop production, especially for commercial investments, because of its general effects on access and security; it has deterred investments in land development to support agricultural production” (Ghana Compact).

Many compacts assert that if the land is not used for large-scale commercial monocropping, it is being used improperly. For example, in Rwanda, “land fragmentation” is cited in the Compact as a critical barrier to development because farmers’ “plots are too small to produce a marketable surplus to invest in future production” (Rwanda Compact). In Lesotho, the compact notes how most land is held traditionally, with most transfers of land occurring informally. As a result, “there is no comprehensive land registry, nor a database of agricultural land parcels. This effectively prohibits the use of land for collateral, especially given the uncertainty relating to the transferability of leases and the reputational risk that a lending institution would incur were it to have to repossess land” (Lesotho Compact). Here, we see smallholder-held land become ‘collateral’ in debt schemes from large corporations. In Ghana as well, “the land tenure system is a key agriculture and crop production challenge… It is a constraint to crop production, especially for commercial investments, because of its general effects on access and security; it has deterred investments in land development to support agricultural production” (Ghana Compact).

While the compacts lament smallholder land tenure, their alternatives threaten smallholder land sovereignty. Viewing smallholders’ tenure as inefficient, the compacts open the door for continued large-scale land grabs from governments and corporations that dispossess smallholders of their land (Cotula 2009, Nyantakyi-Frimpong & Benzer Kerr, 2014). The very notion of cultivated vs arable land hinges on certain notions of permitted forms of agriculture that make smallholder agriculture, pastoralism, agroforestry, hunter-gathering, and other food systems invisible, exposing them to vulnerabilities of land expropriation and tenure insecurity. For example, Rwanda is slated for a massive increase in land dedicated to nearly 1 million hectares of industrial farming. According to the Rwandan government, the country has only 1.4 million hectares of arable land in total. Even then, 1.6 million hectares were reported to be cultivated before the Dakar II plans (Rwanda Environment Management Authority). This leads to questions of where this proposed increase of cultivated land will come from and how it will impact the environment and the land rights of current land users.

While small-scale farmers have stewarded and adapted their own lands, understanding the importance of biodiversity for thriving food systems, the compacts propose to acquire new land mainly for monocropping a few key crops, primarily maize, rice, and soybeans.

This can explain the need for significantly more land under irrigation, as these crops, especially rice, require large amounts of water. However, on one of the world’s driest continents, such an increase in irrigation is expected to lead to a dramatic increase in pressure on water resources in many countries. Drylands comprise about 43 per cent of Africa’s land surface, account for about 75 per cent of the area used for agriculture and are home to about 50 per cent of the population, including many of the most vulnerable rural households. Vulnerability in drylands is rising, jeopardising the livelihood of millions (Cervigni & Morris, 2016). While small-scale farmers can benefit significantly from irrigation (e.g. drip irrigation for vegetable production, enabling several crops to be grown in a year), the compacts’ plans emphasise large-scale irrigation for industrial-scale monoculture production of cash crops.

Tanzania provides a case study of how the compacts seek to change how land is managed for African smallholders. The compact focuses on increasing the production of wheat, seed oils, and vegetables and, in doing so, seeks a cultivable area increase of 1.2 million hectares. While “most of the land earmarked for agriculture and agro-processing is still under the ownership of village councils, yet to be transferred, planned, and surveyed” (Tanzania Compact), the Compact sees better use in block farming and monocropping of the three value chains mentioned. The government and private sector are critical agents in dispossessing smallholders from their land by “investing in identifying and acquiring land available for large scale block farming and installing irrigation infrastructure and dams” (Tanzania Compact). Ultimately, the Compact itself becomes an invitation for the private sector to secure large-scale land grabs with full government support: “The government is keen to partner with the private sector in the land clearing and administration, formalisation, and registration that is going on, through provision of land surveying and cadastre mapping technologies and services” (Tanzania Compact).

As seen through these several examples, in addition to funnelling money towards agro-industrialisation, the compacts could kick-start a wave of large-scale land acquisitions across the continent, favouring large-scale block farms and monocropping over smallholder tenure. Besides the issue of terrestrial land grabbing, there’s a growing trend of offshore land grabbing, exemplified by developments in Benin. The Benin Compact outlines plans for “aquaculture development, which includes the construction of ten aquapoles, each covering 25 hectares, planned to be completed by 2026.” The compacts seek to radically restructure how natural resources are used on and off the continent.

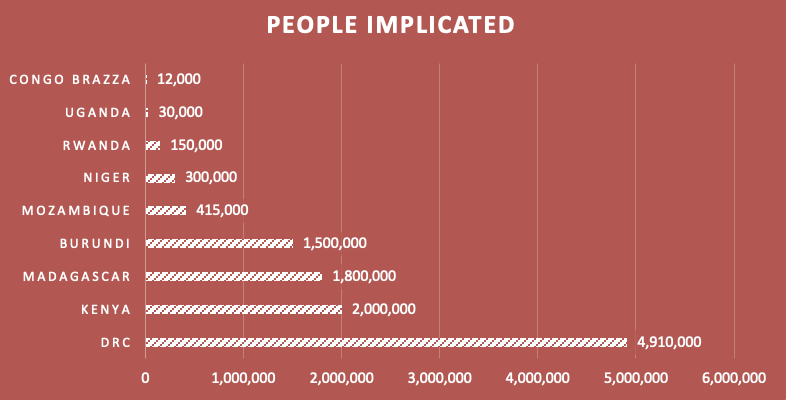

3.3 PEOPLE

The compacts not only implicate money and land but also the small-scale farmers themselves in new production paradigms. Ultimately, through all the interventions mentioned, the compacts seek to transform the identity of the smallholder farmer in Africa. All in all, the compacts call for the involvement of 11,117,000 smallholders in industrialised production schemes. In block farming projects, they serve as contract farmers supplying a commodity crop such as rice to an industrial scale “anchor farm” for marketing, with little control over their land, crop choices or prices. How smallholders exert sovereignty over their food is altered through the creation of new jobs, the provision of improved seeds and mechanised irrigation equipment, and a variety of other programs. For example, in Kenya, the compact proposes to “transform 2 million poor farmers into surplus producers through input finance and intensive agricultural extension support” (Kenya Compact). Overall, such a dramatic shift shows how the compacts envision a completely reorganised rural world for Africa.

The chart below indicates figures from the nine countries where large numbers of farming households are involved. (Some compacts refer to No. of farmers, others to No. of households). See Appendix C for more details.

3.4 SEEDS

Another critical component of the compacts is the proposed establishment of ‘formal seed systems’ for smallholders. In Tanzania, Ghana, Egypt, Nigeria, Rwanda, Somalia, and Benin specifically, certified seed schemes are a direct goal of the compacts. Formal seed systems can directly undermine smallholders who rely on traditional seed systems that protect their ability to grow what they want, when, and how they want to.

Formal and certified seed systems open the door for multinational seed companies to plant themselves into the lives of smallholders. For example, in Lesotho, the plan calls for more certified seeds. It demonstrates the threats posed by formal seed systems: “Over time, many of the traditional indigenous varieties have been replaced by the commercial varieties for which seeds and seedlings are readily available, though most are imported from South Africa and are not especially suited to Lesotho’s climate and soils” (Lesotho Compact).

Another example of the drive for formal seed systems comes from Tanzania, where the Compact seeks to improve seed certification projects already underway, which include the creation of seed farms, seed processing facilities, and seed storing facilities, which a government-regulated seed agency oversees. This agency works strictly with commodity value chains, ensuring their propagation over other crops. In total, $30 million is dedicated to building formal seed systems in Tanzania, with the private sector being targeted as the country’s primary funder for seed certification (Tanzania Compact).

Many African farmer organisations resist the growth of formal certified seed systems due to varied concerns across the continent:

- Cost and Accessibility: Formal systems often have higher costs than traditional or informal seed methods, making it hard for small-scale farmers to afford certified seeds. This could widen inequalities in agriculture.

- Dependency and Control: Critics fear increased reliance on multinational companies or governments for seeds, reducing farmers’ autonomy and resilience, as seen during supply disruptions like the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Threat to Biodiversity: Certified seeds favour limited, uniform crop varieties, potentially harming traditional crop diversity and indigenous seed types adapted to local conditions.

- Displacement of Informal Systems: Formal seed systems might replace traditional seed-saving and exchange practices, which are crucial for the adaptability of African agriculture.

- Marginalisation of Small-Scale Farmers: These systems could favour large or export-oriented farms, side-lining smallholders who constitute the majority of Africa’s agricultural community.

- Lack of Participatory Approaches: The promotion of formal systems is often criticised for not involving local communities and stakeholders, neglecting diverse needs and knowledge.

In summary, opposition stems from concerns about affordability, dependency, biodiversity loss, displacement of traditional practices, marginalisation of small-scale farmers, and non-inclusive development strategies. Critics call for more inclusive, sustainable approaches to serve African farmers’ diverse needs.

Developing laws favouring breeders’ rights also paves the way for genetically modified (GM) crop varieties, which are not permitted in most African countries. GM seeds also pose a significant cost for smallholders who typically produce or share their own seeds. These costs are often prohibitive and widen inequality gaps among farmers (Boafo & Lyons, 2022). Many oppose the introduction of GM crops due to concerns about environmental impact, food sovereignty and security, health and safety risks, economic impacts, ethical and cultural considerations, lack of transparency, and the promotion of alternative, sustainable agricultural practices. These concerns reflect a desire to protect the environment, promote food sovereignty, and ensure the well-being of farmers and consumers across the continent.

3.5 TECHNOLOGY

The replacement of traditional seeds for so-called ‘climate-smart’ varieties (Benin and Somalia Compacts) points out another key element of the compacts’ priorities: a focus on so-called climate-smart agriculture, digital and precision agriculture, mechanisation, and high-tech inputs more generally. Climate-smart agriculture (CSA) is a loosely defined term that seeks to reduce climate impacts by sustainably intensifying the food system. However, the lack of clear guidelines has allowed the concept to be co-opted by agribusiness, leading its practices to be labelled as greenwashing. Small-scale farmers have rejected climate-smart agriculture as another attempt at rebranding and repackaging old solutions that favour big business over food sovereignty (ETC Group, Clay & Zimmerer, 2020).

The compacts for Tanzania, Ghana, Somalia, Benin, Zimbabwe, and Zambia all mention CSA technology. In Somalia, the terms formal or certified seed systems are replaced by “sustainable seed system”, with no real explanation of what makes it sustainable. Digital Ag-Tech systems (a confusing term used by the compacts with no clear definition yet part of their ultimate drive to agricultural industrialisation), E-extension (Sierra Leone, Somalia, and Rwanda Compacts), and precision agriculture (Uganda Compact) were also examples of high-tech projects of the compacts. With the introduction of these practices, concerns arise over data sovereignty, ownership, and equitable access to expensive technologies meant for agricultural development. In Sierra Leone, the purpose of Ag-Tech systems will be to “collect real-time information to support decision making. An agriculture data hub will be built to maximise the insight from different and discrete data sources. These will be used to track progress towards Compact goals. As an approach, the Compact will largely rely on the private sector to implement these initiatives” (Sierra Leone Compact). Here, we can see how high-tech innovations might allow the private sector to influence farming practices under the guise of supporting ‘decision-making.’

3.6 AGROCHEMICALS

Chemical fertilisers and pesticides are standard features of strategies aimed at industrialising agriculture in Africa. Fertilisers represent one of the industries most supported by the AfDB. In 2014, it granted a loan to Dangote – Africa’s richest businessman – of USD 300 million intended for the construction of a crude oil refinery and a fertiliser manufacturing plant. A specific programme is dedicated to increasing farmers’ use of these products: the African Fertiliser Financing Mechanism (AFFM), created in 2006. For the current 2022-2028 period, the expected result is the distribution of 2 million tons of fertiliser and other inputs to 16 million smallholder farmers, so that they apply at least 50 kg per hectare. The priority crops for this program are maize, rice, cassava, soybeans, wheat, sorghum, millet, cowpea, cocoa, coffee, cotton, horticulture and oil palm (GRAIN, 2023). AfDB’s fertiliser program was expanded in 2021 to deal with the high cost and unavailability of synthetic fertiliser and is likely to be a key focus of AfDB’s contribution to the compacts through grants and credits.

Although some compacts mention the importance of increasing farmers’ use of organic fertilisers, they more often advocate the expanded use of inorganic and chemical fertilisers. Like hybrid seeds, chemical fertilisers and pesticides also pose a significant cost burden to small-scale farmers. In Rwanda, where the Compact seeks to raise a massive $189 million for fertilisers alone, the average fertiliser use per hectare is suggested to rise by 20%, with total production reaching 84,000 MT per year. Yet in smaller, poorer countries unable to produce their own inorganic fertilisers, an increase in synthetic inputs also means increased imports and dependency.

Many African small-scale farmer organisations resist synthetic fertilisers due to concerns over:

- Cost and Affordability: Synthetic fertilisers are often too expensive for small-scale farmers, and the governments that subsidise them, exacerbating economic strains and agricultural inequalities.

- Environmental Degradation: Their use can lead to soil erosion, water pollution, and biodiversity loss, damaging ecosystems and agriculture sustainability.

- Soil Health: Synthetic fertilisers fail to enhance long-term soil fertility, contributing to degradation and nutrient imbalance. Sustainable practices like organic matter addition and crop rotation are advocated instead.

- Dependency: Reliance on synthetic fertilisers fosters dependency on external inputs and multinational companies, undermining farmer autonomy and resilience.

- Health Risks: Exposure to synthetic fertilisers poses risks of respiratory issues, skin irritation, and other health problems, promoting a shift towards safer agroecological approaches.

- Climate Change: The production and use of synthetic fertilisers contribute to greenhouse gas emissions. Reducing their use in favour of agroecological methods can aid in climate change mitigation.

In summary, the opposition to synthetic fertilisers centres on affordability, environmental impact, soil health, dependency, health risks, and climate change, with a push for more sustainable, equitable, and farmer-friendly practices.

4. CONCLUSIONS

In an era where advocates for large-scale development of African agriculture are shedding terminology relating to the green revolution, the Dakar II compacts provide an important example of how things may, or may not, be changing. While none of the compacts call explicitly for a new green revolution, the strategies laid out are much the same. The compacts repackage the same old strategies that have been proven unsuccessful time and time again, only now with a more aggressive focus on agribusiness-led industrial farms. While the actors and the strategies remain the same, the terminology and importantly budget are changing this time around. Ultimately, the compacts overwhelmingly rely on industrialisation as their method for agricultural development and, in doing so, present renewed threats to small-scale farmers’ sovereignty on the continent.

With a claimed committed budget of $30 billion so far and a total estimated budget of over $60 billion, the proposed investment in Dakar II far outspends the $1 billion spent on the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (Wise, 2021) or the estimated $1 billion per year African governments spend on input subsidies. The compacts promote terms like climate-smart, nature-based, and digital agriculture, which may appear to offer modern, high-tech solutions to today’s challenges. However, these terms mask the underlying agenda: the industrialisation of African agriculture, benefitting multinational corporations, often to the detriment of small-scale farmers and the environment.

Additionally, while the Green Revolution for Africa has largely relied on agricultural intensification as its main approach to increase yields, we see that the compacts combine this with an agricultural extensification approach. That is, instead of seeking higher yields but using different inputs such as hybrid seeds and chemical fertilisers and pesticides, this new approach seeks higher production by also significantly increasing the area of land cultivated. This strategy dramatically differs from former approaches and has potentially dire consequences for the land rights of current land users.

Despite the wide-ranging social, ecological, and agricultural systems present in the 40 countries involved, the solutions offered by the compacts remain largely uniform. Like the Green Revolution for Africa, these compacts demonstrate a one-size-fits-all approach to development, overlooking the necessary nuances for achieving just and inclusive progress. Key commodity crops, mechanised inputs, and standardised land tenure practices all streamline diverse processes into one steamrolled attempt for industrialisation. Not just what the compacts say but how they are written suggests a one-size-fits-all approach without real farmers’ interests in mind. Complied and produced by Dalberg Global Development Advisors, a high-profile strategy and policy advisory consultancy, the compacts follow a similar writing format for each country, and are riddled with factual errors, typos, and overall poor writing and presentation. Countries are often mixed up with one other, paragraphs end abruptly or are repeated, and number values are sometimes just left as xxx or “to be filled in later.” Moreover, the quality of writing and depth of detail is significantly lower on francophone country compacts written in French, suggesting insufficient French-speaking consultants were engaged on the project. The writing’s lack of thought and attention reflects a similar lack of care in the proposed solutions. This prompts us to question the true beneficiaries of these compacts. Are they genuinely aimed at supporting small-scale farmers, as claimed, or do they primarily serve the agenda of industrialising African agriculture? Additionally, we must consider whether the Dakar II initiative, with its 40-country compacts and touted mobilisation of $61 billion, represents well-thought-out plans or a large-scale public relations effort/pitch for inward investment.

The President of Ireland, Michael D. Higgins, provided a lone voice of reason at the Dakar II Summit in January 2023, where this all began. He challenged the renewed focus on monocultural industrial farming, advising, “We must address how has it come to pass that the people of Africa are so dependent on three food staples and that the food production and distribution model in place is so deeply flawed.” He called for a shift in mindset, “We now need best ecological practices in agriculture, including agroecology, to become widespread. This is substantially different from mere adjustments to the productionist agronomy model, a colonially imposed food system, which has exacerbated food insecurity by creating over-dependence on a small number of staples and an over-reliance on imported fertiliser, pesticide and seeds. Agroecological models show us a path away from dependency and insecurity, towards a decolonised agronomy. We must make concerted efforts to ensure the removal of barriers to diverse agricultural development in Africa, as in, for example, offered through agroecology, if Africans are to unlock Africa’s potential.” (Higgins, 2023).

5. REFERENCES

Adesina, A. (2018). Speech by Dr. Akinwumi A. Adesina, President, African Development Bank Group Distinguished Speaker at the 94th annual US Department of Agriculture Outlook Forum – “The Roots of Prosperity” https://www.afdb.org/fr/news-and-events/speech-delivered-by-dr-akinwumi-a-adesina-president-african-development-bank-group-distinguished-speaker-at-the-94th-annual-us-department-of-agriculture-outlook-forum-the-roots-of-prosperity-17868

Adesina, A. (2022). Speech by Dr. Akinwumi A. Adesina, President, African Development Bank Group YARA’s Knowledge Exchange Event September 29, 2022, Oslo, Norway. https://www.afdb.org/sites/default/files/2022_09_29_speech_dr._akinwumi_adesina_yaras_knowledge_exchange76.pdf

African Development Bank. (2023a). Dakar 2 Summit: Development partners to commit $30 billion to boost food production in Africa. AfDB. https://www.afdb.org/en/news-and-events/press-releases/dakar-2-summit-development-partners-commit-30-billion-boost-food-production-africa-58598

African Development Bank. (2023b). African leaders declare support for African Development Bank’s food summit outcome, call for urgent implementation. AfDB. https://www.afdb.org/en/news-and-events/press-releases/african-leaders-declare-support-african-development-banks-food-summit-outcome-call-urgent-implementation-59172

African Development Bank. (2024). Group and research centres to transform African agriculture and improve food security. https://www.afdb.org/en/news-and-events/press-releases/african-development-bank-group-and-research-centres-transform-african-agriculture-and-improve-food-security-68239

Blair, R., Kimbugwe, K., Koleros, A., Mangheni, M., Narayan, Tulika., Usmani, F. (2021). Partnership for Inclusive Agricultural Transformation in Africa, Final Evaluation. Mathematica. https://www.iatp.org/blog/202007/failing-africas-farmers-new-report-shows-africas-green-revolution-failing-its-own-terms

Boafo, J., Lyons, K. (2022). The Rhetoric and Farmers’ Lived Realities of the Green Revolution in Africa: Case Study of the Brong Ahafo Region in Ghana. Journal of Asian and African Studies. 57(3). 406-423.

Cervigni, R., and Morris, M. (2016). Confronting Drought in Africa’s Drylands. Africa Development Forum, World Bank Group. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/6c1d090c-df47-559b-b8d9-753bb57541a7/content.

CIFOR/ICRAF (2015). Deforestation and forest degradation in the Congo Basin: State of knowledge, current causes and perspectives. https://www.cifor.org/knowledge/publication/5894/#:~:text=Slash%2Dand%2Dburn%20agriculture%2C,the%20main%20causes%20of%20deforestation.

Clay, N., Zimmerer KS. (2020). Who is resilient in Africa’s Green Revolution? Sustainable Intensification and Climate Smart Agriculture in Rwanda. Land use policy 97. 10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104558

Congo Basin Forest Partnership, CBFP (2023). ‘First lung’: This rainforest could be the world’s most important carbon sink. Euronews. https://pfbc-cbfp.org/news-partner/Euronews-23.html

Cotula, L. (2009). Land Grab Or Development Opportunity? Agricultural Investment and International Land Deals in Africa. Report for FAO, IFAD, and IIED. https://www.iied.org/12561iied

ETC Group. (2023). Statement on the Dakar 2 Summit : “Climate smart agriculture” will worsen the climate crisis. Assess Technology, ETC Group. https://assess.technology/featured/statement-dakar-summit-climate-smart-agriculture-climate-crisis/

FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO. (2023). The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2023. Urbanisation, agrifood systems transformation and healthy diets across the rural–urban continuum. Rome, FAO. https://doi.org/10.4060/cc3017en

GRAIN (2023). The AfDB strategy to agro-industrialise Africa. GRAIN. https://grain.org/en/article/7016-the-afdb-strategy-to-agro-industrialise-africa#_edn16

Higgins (2023). Speech Delivered by the President of Ireland, Michael D. Higgins – Feed Africa Summit: Food Sovereignty and Resilience – 25-27 January 2023. Dakar, Senegal. https://www.afdb.org/fr/news-and-events/speeches/speech-delivered-president-ireland-michael-d-higgins-feed-africa-summit-food-sovereignty-and-resilience-25-27-january-2023-dakar-senegal-58431

Nyantakyi-Frimpong, H. and Bezner Kerr, R. (2014). A Political Ecology of High-Input Agriculture in Northern Ghana. African Geographical Review.

Prášková, D.M. & Novotný, J. (2021) The rise and fall of the New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition: a tale of two discourses, Third World Quarterly, 42:8, 1751-1769, DOI: 10.1080/01436597.2021.1917355

Rwanda Environment Management Authority (REMA). Rwanda State of Environment and Outlook Report chp. III. Land Use and Agriculture. REMA. https://www.rema.gov.rw/soe/chap3.php

Wise, T. (2021). Throwing good money after bad: Failing Green Revolution program readies billion-dollar fund drive. IATP. https://www.iatp.org/throwing-good-money-after-bad#:~:text=The%20organization%2C%20which%20has%20spent,key%20platform%20for%20its%20fundraising.

Download full report in PDF here

6. COUNTRY FOOD AND AGRICULTURE DELIVERY COMPACTS

All 40 country compacts are available on the African Development Bank website here: https://www.afdb.org/en/dakar-2-summit-feed-africa-food-sovereignty-and-resilience/compacts

Individual country compacts are linked below:

Angola https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/angola-country-food-and-agriculture-delivery-compact

Benin https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/benin-pacte-pour-lalimentation-et-lagriculture

Botswana https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/botswana-country-food-and-agriculture-delivery-compact

Burundi https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/burundi-pacte-pour-lalimentation-et-lagriculture

Cabo Verde https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/cabo-verde-pacte-pour-lalimentation-et-lagriculture

Cameroun https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/cameroun-pacte-pour-lalimentation-et-lagriculture

Comoros https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/comores-pacte-pour-lalimentation-et-lagriculture

Congo https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/congo-pacte-pour-lalimentation-et-lagriculture

Cote d’Ivoire https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/cote-divoire-pacte-pour-lalimentation-et-lagriculture

Djibouti https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/djibouti-pacte-pour-lalimentation-et-lagriculture

Egypt https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/egypt-country-food-and-agriculture-delivery-compact

Ethiopia https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/ethiopia-country-food-and-agriculture-delivery-compact

Gabon https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/gabon-pacte-pour-lalimentation-et-lagriculture

Gambia https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/gambia-country-food-and-agriculture-delivery-compact

Ghana https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/ghana-country-food-and-agriculture-delivery-compact

Guinee-Bissau https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/guinee-bissau-pacte-pour-lalimentation-et-lagriculture

Kenya https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/kenya-country-food-and-agriculture-delivery-compact

Lesotho https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/lesotho-country-food-and-agriculture-delivery-compact

Liberia https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/liberia-country-food-and-agriculture-delivery-compact

Madagascar https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/madagascar-pacte-pour-lalimentation-et-lagriculture

Malawi https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/malawi-country-food-and-agriculture-delivery-compact

Mauritanie https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/mauritanie-pacte-pour-lalimentation-et-lagriculture

Mozambique https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/mozambique-country-food-and-agriculture-delivery-compact

Niger https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/niger-pacte-pour-lalimentation-et-lagriculture

Nigeria https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/nigeria-country-food-and-agriculture-delivery-compact

Republique Centrafricaine https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/republique-centrafricaine-pacte-pour-lalimentation-et-lagriculture

Republique de Guinee Equatoriale https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/republique-de-guinee-equatoriale-pacte-pour-lalimentation-et-lagriculture

Republique Democratique du Congo https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/republique-democratique-du-congo-pacte-pour-lalimentation-et-lagriculture

Rwanda https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/rwanda-country-food-and-agriculture-delivery-compact

Senegal https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/senegal-pacte-pour-lalimentation-et-lagriculture

Sierra Leone https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/sierra-leone-country-food-and-agriculture-delivery-compact

Somalia https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/somalia-country-food-and-agriculture-delivery-compact

South Sudan https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/south-sudan-country-food-and-agriculture-delivery-compact

Tanzania https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/tanzania-country-food-and-agriculture-delivery-compact

Tchad https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/tchad-pacte-pour-lalimentation-et-lagriculture

Togo https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/togo-pacte-pour-lalimentation-et-lagriculture

Tunisie https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/tunisie-pacte-pour-lalimentation-et-lagriculture

Uganda https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/uganda-country-food-and-agriculture-delivery-compact

Zambia https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/zambia-country-food-and-agriculture-delivery-compact

Zimbabwe https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/zimbabwe-country-food-and-agriculture-delivery-compact

[…] analyzed each of the 40 country compacts and summarized the proposed plans in its new report, some of which include the expansion of large-scale monocropping and the establishment of formal […]

[…] evaluated each of the 40 nation compacts and summed up the proposed strategies in its brand-new reporta few of that include the growth of massive monocropping and the facility of official licensed seed […]

[…] now scrutinised the 40 “country compacts” proposed under the Dakar II initiative in a new report. Our findings reveal a worrying trend towards consolidating land for industrial agriculture, […]